What is "hitting the wall" and how do I avoid it?

If you bonk or hit the wall during exercise, you’ll know about it.

Maybe you’ve avoided bonking so far – lucky you. What does it feel like? Hitting the wall, or "bonking", usually has a physical and a mental aspect. You feel your body slowing, you feel fatigued, weak, and the idea of speeding up feels impossible. Your mind slips into a negative state: you may feel frustrated or hopeless and you may be tempted to quit.

So, what is causing you to hit the wall?

This is where we’ll get a bit science-y (sorry).

During endurance exercise, especially when you’re exercising at a high intensity, your body relies heavily on energy from glucose (i.e. carbohydrates, or sugar). Your muscles and liver store glucose in the form of glycogen, which is an accessible (but finite) energy reserve. You can supply your muscles with extra glucose by consuming carbohydrate-rich food and drink during exercise, which are quickly absorbed and used your body.

You get into “bonking” territory when our muscle glycogen levels are reduced, and your energy demands are larger than the rate of glucose that your muscles and food/drink can supply.

When you start a high-intensity workout or race, your body prefers to use more glucose and glycogen for energy than it does fat. But as these sources run low, your body begins to burn more fat, amino acids, and ketones. Sports science nerds call this a metabolic shift.

This shift is less efficient but necessary.

This is the junction where you might take an unwanted turn-off into Fatigue City.

The shift in energy usage can decrease performance and everything starts to feel HARD.

Obviously, you never want to visit Fatigue City.

Here’s how to take a detour:

-

It starts with training. You can improve your body’s ability to use fat as fuel. The fancy term is “improving metabolic flexibility”. You can train for this by completing some long, slow runs that rely less on carbs for energy (this is where Energy Nut Butter can fit into your training), or by completing some sessions in a fasted state.

-

Pre-race nutrition. You want to start your race with full glycogen stores. That means eating enough carbohydrates in the days before the race. Don’t go crazy here (you don’t need to shovel pasta in every meal), but don’t skip the carbs.

-

Race (and training) nutrition. Bonking usually happens because you (1) didn’t have a nutrition plan (2) had a nutrition plan but didn’t stick to it, or (3) had gastro-intestinal issues meaning you couldn’t get food or drink down. Practice this during training. See the Q&As below.

-

Hydrate enough. Getting dehydrated is like buying a first-class ticket to Fatigue City. Drinking enough will help you to digest any food better, it’ll maintain your electrolyte balance, and support muscle function. Drink to thirst, please.

- Know your limits. Don’t be a hero, stick to a pace that you can sustain for the given distance and intensity. We’ve all done it, and it doesn’t end well.

Well prevention is all great, but let’s be real – you’re probably going to mess it up at some stage, we all do :)

Here's what to do if you find yourself slogging down the Main Street of Fatigue City:

-

Look for street signs. This sounds obvious, but first step is to realise that you’re in Fatigue City! Time to act.

-

Get carbs in. This is when chews, sports drinks, gels and even lollies can help. You need glucose, pronto. You know why they put Coke at the last aid station at a marathon? ‘Cos everyone is hitting the wall and bottled sugar helps.

-

Reduce exercise intensity. This is a strategic call and can get you to the finish line. Slow down your pace for a bit until you can get more energy into you.

- Use your mind. Our perspective quickly changes when we feel drained of energy. Focus on achieving simple goals. Recycle your favourite mantra over and over in your head – whatever mental strategy it takes to keep your mindset positive.

Why your body ‘hits the wall’ and how to deal with it is a complicated topic.

We've covered the basics, but if you’re looking for more depth, check out the Q&As below.

Got questions?

We've tried to answer them here. Check the section below for links to other resources.

It depends. There are three things to consider:

- The duration of the event/race

- Intended exercise intensity (all-out effort, hard effort, moderate, easy)

- Your personal preferences.

Generally, the longer the event, the lower the exercise intensity.

For example, runners racing a 5km would compete at an ‘all-out’ effort. Half or full marathon runners could sustain a ‘hard’ effort for a few hours. Ultra-distance athletes simply can’t sustain a hard effort for many hours, so they compete at a lower exercise intensity (e.g. moderate effort).

During a 5K or 10K run, you don’t need to consume fuel as your muscle glycogen stores can cover your energy needs. During a half or full marathon, carbohydrates will be your primary (or only) fuel source.

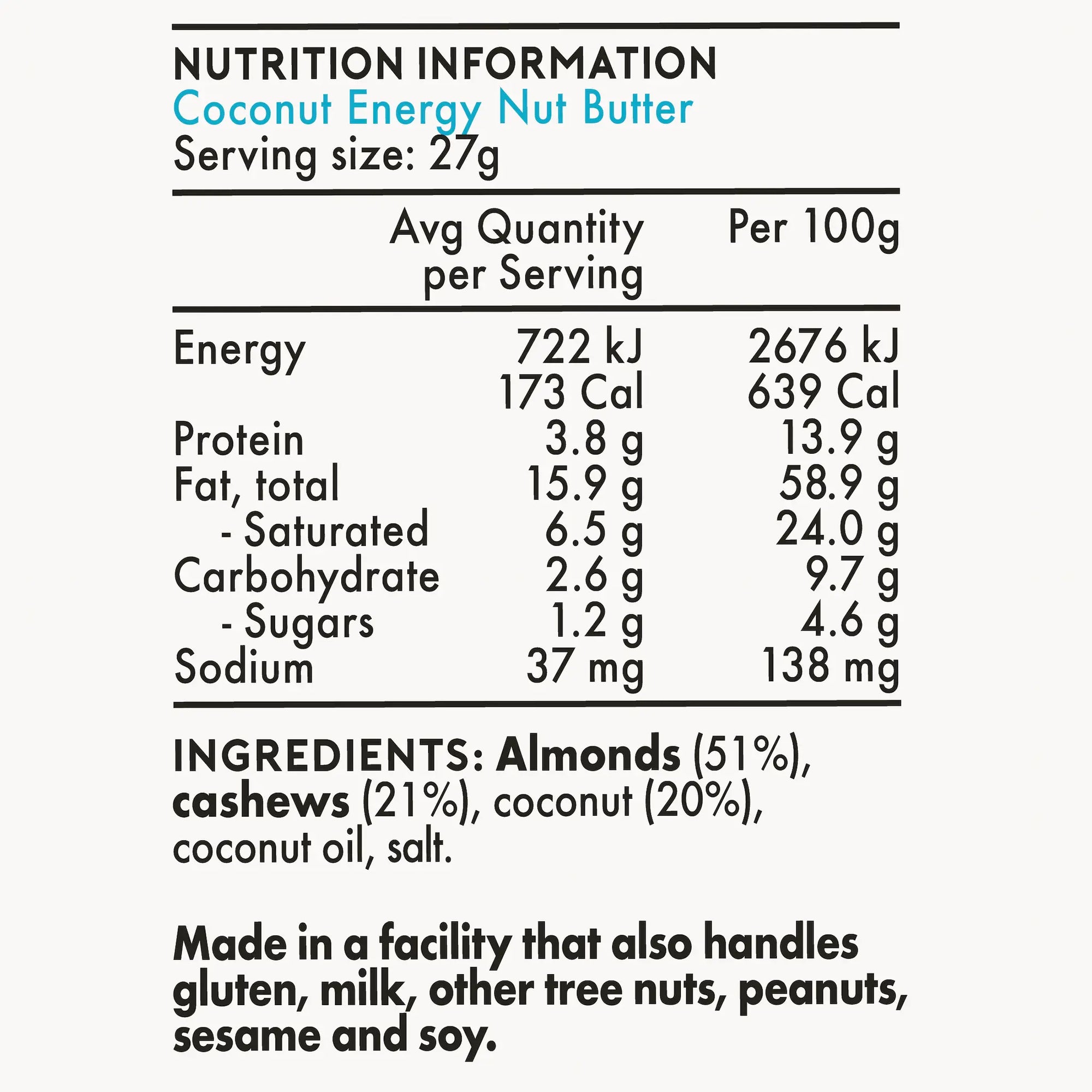

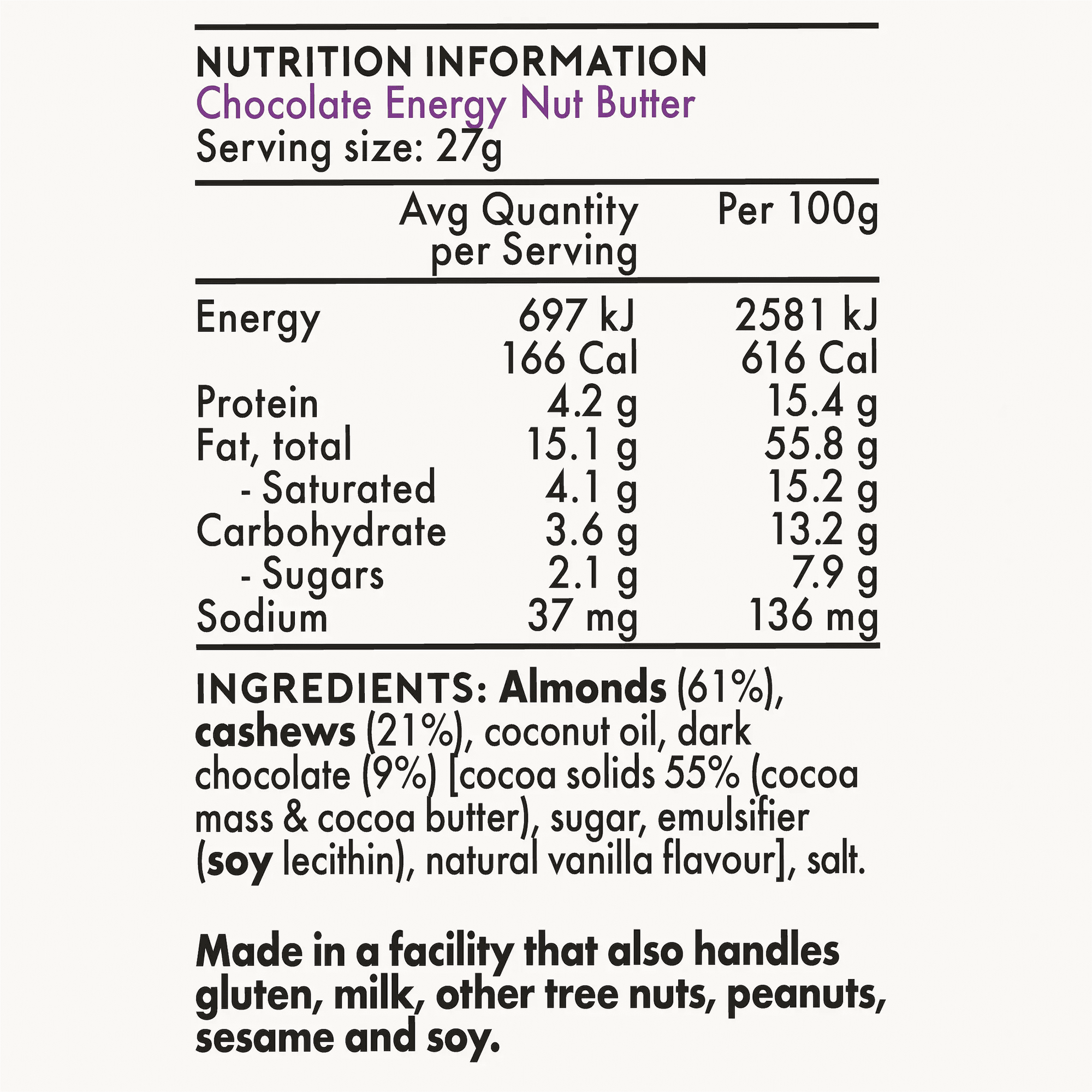

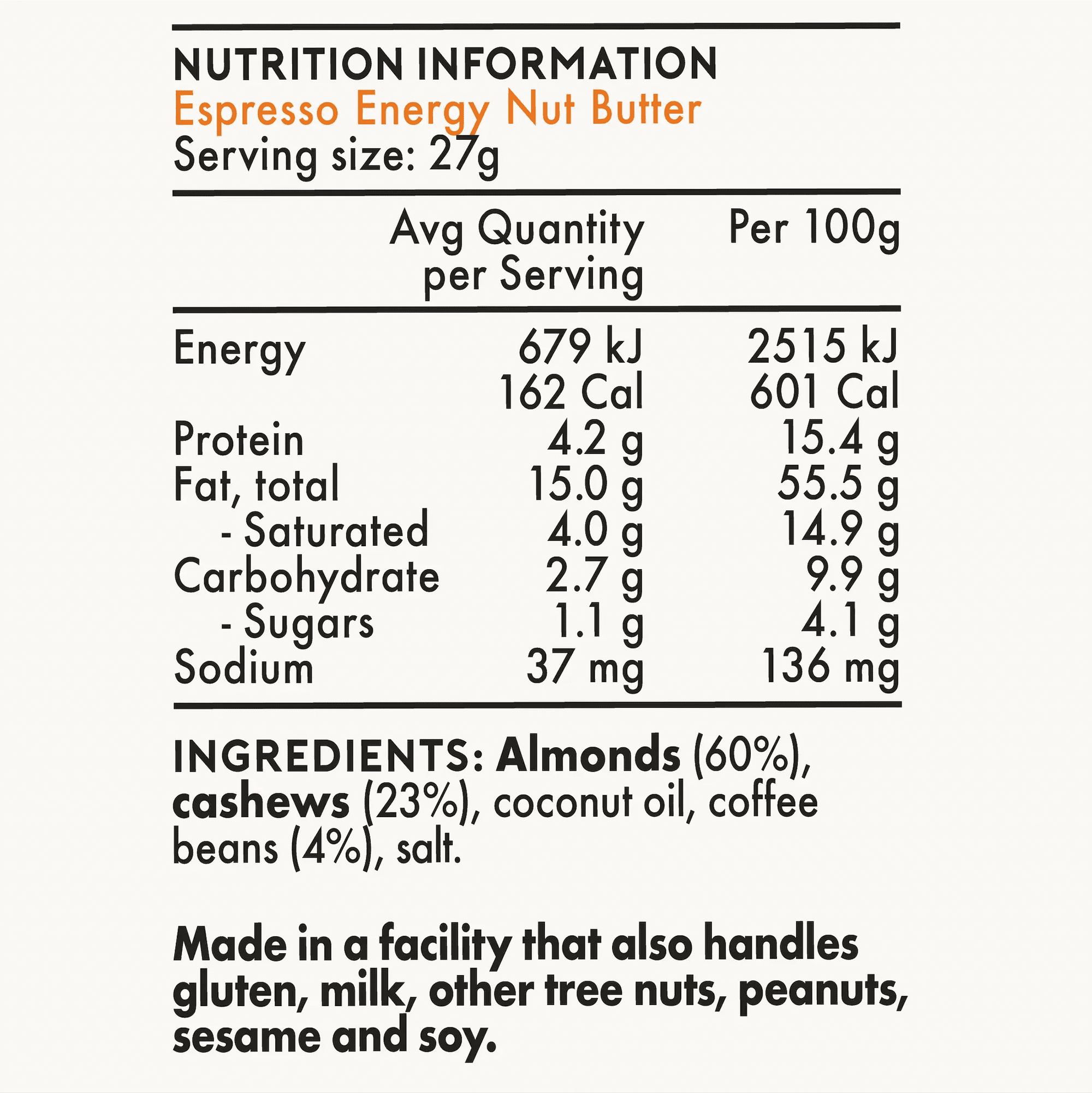

Ultra-distance athletes have more fuelling options. Because they are moving at a lower intensity, they can afford to eat some foods and drink containing fat and protein (for example Energy Nut Butter). This can be a smart option, as high amounts of concentrated carbohydrates can cause gut issues.

Read more on gastro intestinal distress here.

No. Most sports energy products contain a mixture of fructose and glucose or a complex carbohydrate. Read about multiple transportable carbohydrates to learn more.

Many sports products contain an ingredient called maltodextrin. This is a complex carbohydrate that eventually breaks down into glucose molecules. It takes your body some extra time to break down this energy, so that you don’t get a massive sugar rush.

No. Your body reserves some glycogen for critical functions – for example brain function.

Fun fact: You don’t need a gel 15-min before the start of your race. You have a full store of glycogen sitting in your muscles, ready to go. If anything, the gel will spike your blood sugar levels and you’ll feel crappy 20-min later (not ideal).

For exercise longer than 90 minutes, it’s best to start fuelling about 45 to 75 minutes into the race, to prevent your muscle glycogen levels from dropping too low.

If you are a high-performance athlete competing in events less than 75-minutes (for example, a half marathon runner), even a mouth rinse or small sip of a carbohydrate drink may be enough to improve performance, without worrying about consuming large amounts of energy during your race.

Yes it can, but it’s not your body’s preferred choice. It’s a bit like starting a campfire and choosing to burn your wooden cabin instead of the logs outside.

Similarly, during exercise, your body prioritises burning glycogen and fat. Amino acids are called upon when these primary fuel sources start to dwindle or when the intensity of your workout is so high that your body needs extra fuel.

However, during ultra-endurance events, incorporating protein can be beneficial. It helps to prevent some muscle breakdown and provides a steadier, slow-burning energy source to complement carbohydrates and fats. It also plays a role in managing hunger and stabilising blood sugar levels.

At a low exercise intensity, your body’s preferred fuel is fat.

It’s only when we approach a moderate intensity (50% to 70% of VO2max) that our body starts to rely more heavily on muscle glycogen (and any carb-rich food or drink we consume) for energy.

The proportion of fats to glucose that you burn during exercise depends on many factors: genetic makeup, level of training, if you’ve followed a nutrition strategy (e.g. train-low). At a hard race pace, for example, marathon pace, you can burn anywhere from 0.1g to 1.5g of fat per minute.

You may also like...

- What is muscle glycogen?

- Gastro-intestinal symptoms and gut training

- Nutrition planning for ultras and adventure racing

- What is maltodextrin?

- What are multiple transportable carbohydrates?

- What are hydrogels?

- What are monosaccharides and oligosaccharides?

- Maximising performance with Energy Nut Butter: A Guide for Endurance Exercise

- Energy Nut Butter and LCHF and Ketogenic diets