Breaking a drinking habit: Overhydration during exercise

Chances are, you’ve experienced mild dehydration during exercise – but did you know you can overhydrate?

Overhydration is when you drink[1] more fluid than you’re losing from your sweat and pee. This could disrupt the balance of electrolytes in your blood.

Overhydration can escalate into a medical issue known as Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia (EAH), where sodium levels in your blood fall dangerously low. The extra fluid can cause the cells in your brain and lungs to swell to levels that can be fatal in severe cases.

Diagnosing EAH involves measuring the sodium levels in your blood. But this is hardly practical during exercise or a race, making it challenging to determine overhydration on the spot.

But there are a few early signs of overhydration that can help you to sidestep the serious consequences of EAH.

Signs you might be overhydrating

- Puffy fingers (or feet). Do your fingers turn into sausages on your long workouts or races? This can be a sign that you’re drinking too much fluid.

- You weigh more after your run. Provided you haven’t stopped for a hearty meal – this is a sign that you may be overhydrating.

- You’re drinking to a schedule, not to thirst. The fear of getting dehydrated can backfire! Make sure to ask yourself whether you need water because (1) you’re thirsty or (2) you need to wash food / energy down. If it’s neither of those things, maybe you don’t need to drink just yet.

- Your pee is clear or very pale yellow.

- Fatigue and reduced performance. You are unable to sustain a given pace.

- Nausea and headache.

- Muscle cramps and tremors. Often mistaken as dehydration.

You’ll notice the symptoms of overhydration overlap those of dehydration. People who are experiencing muscle cramps or headaches might assume they're dehydrated and drink even more, unwittingly worsening their condition.

This misunderstanding underscores the importance of recognising signs of overhydration vs dehydration.

Approach your hydration as a response to thirst, not as a scheduled activity.

During prolonged exercise, check in with yourself every 20-30 minutes and ask yourself: “Am I thirsty?” and act from there. See the Q&A below for more about this.

Overhydration in different sports

Fortunately, serious cases of hyponatremia aren’t common, but instances of athletes overhydrating are increasing in some sports. Endurance athletes participating in events or training over 4 hours are more likely to overhydrate. Think ultra-runners, Ironman triathletes, hikers, and military personnel.

Instances of overhydration are also starting to increase in team sports (rugby, football, rowing) and even lower intensity activities such as yoga. [2]

The sport with the highest incidence of overhydration is ultra-running, especially 100-mile races. In these events, athletes are usually moving at a slower pace – which means they’re sweating less. But they can have plenty of opportunities to drink. They usually carry water with them and can replenish fluids at aid stations.

Some event organisers try to monitor overhydration by weighing participants before the race and at the finish line. Participants that weigh more at the finish line, but have no other symptoms, may be asked to:

- Eat salty foods;

- Refrain from drinking until they have urinated.

If you have serious symptoms, the event medical crew can administer emergency treatment to normalise the serum sodium levels in your blood.

What about the role of electrolyte drinks?

Electrolyte drinks replenish minerals (the most important being sodium) lost via your sweat. However, all electrolyte drinks have a lower salt concentration than your blood.

This means that, despite their benefits, electrolyte drinks will not be sufficient to prevent overhydration if you consume them in large amounts during exercise.

To learn more, check out the Q&A section below.

To sum up, overhydrating during exercise can lead to Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia. Most of the time, people are asymptomatic. But in severe cases, it can result in serious health complications. Remember to listen to your body and drink to thirst during endurance training and events.

We’ve compiled a set of related questions below for further information.

[1] There is the possibility of hyponatremia being caused by large losses of sodium via sweat, but in almost all cases, it is caused by drinking too much fluid.

Got questions?

We've tried to answer them here. Check the section below for links to other resources.

The Consensus Statement on Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia

(2015) says:

“Modest to moderate levels of dehydration are tolerable and pose little risk to life in otherwise healthy individuals.

Laboratory and field studies indicate that fluid deficits less than and up to a volume approximately equal to 3% of normal body mass can be tolerated without reduction in endurance performance or muscular power when in cool to temperate (-10 C to 20 C) temperatures.

Therefore, aggressive drinking to prevent dehydration is unnecessary and carries with it greater risk of developing symptomatic Exercise Associated Hyponatremia.”

Our blood contains dissolved electrolytes such as sodium and chloride.

These electrolytes are essential for the body to function correctly. They help to:

- Regulate nerve and muscle function

- Balance blood acidity and pressure

- Rebuild damaged tissue

- Hydrate the body.

Our kidneys work to keep the electrolyte concentrations in our blood constant despite changes in our body. For example, when we sweat, we lose electrolytes, and the kidneys help to compensate for this loss.

Maintaining the ‘saltiness’ or right balance of electrolytes in our blood is crucial for our health and well being.

All fluid that you drink is absorbed into the bloodstream via the small intestine.

If you overhydrate, you place unnecessary pressure on your kidneys. The kidneys work to filter the extra fluid from your blood so you can get rid of it in your urine. But there’s a limit to how quickly they can work. If you drink more than your kidneys can process, this will contribute to the dilution of sodium in your blood.

When the sodium in your blood becomes diluted, water starts to enter your body’s cells to balance the sodium levels inside and outside the cells. This causes the cells to swell.

In severe cases of hyponatremia, the cells in the brain begin to swell. This is dangerous because the skull doesn’t allow for expansion. Swollen brain cells can lead to increased pressure inside the skull, which can cause headaches, confusion, and seizures. In extreme cases, it can be life-threatening.

Hydration is important during endurance and ultra-distance events, particularly in hot and humid conditions.

If you’re hydrating based on a schedule in your training and racing (for example, aiming to consume a certain amount of fluid every 20 to 30 minutes), you could inadvertently overhydrate. Instead, you should be checking in with yourself on a regular schedule – asking yourself “am I thirsty?” and then consume fluid if you are.

We are all different when it comes to sweating, both in fluid loss and sodium loss.

Consuming products with sodium can help to replace some (not all) of the sodium you’re losing via sweat. Your blood contains other minerals (e.g. calcium, magnesium, and potassium), but these are less important to replenish during exercise.

If you have a goal of replacing sweat sodium losses, start with a target rate of 500-1,000 mg of sodium per hour.

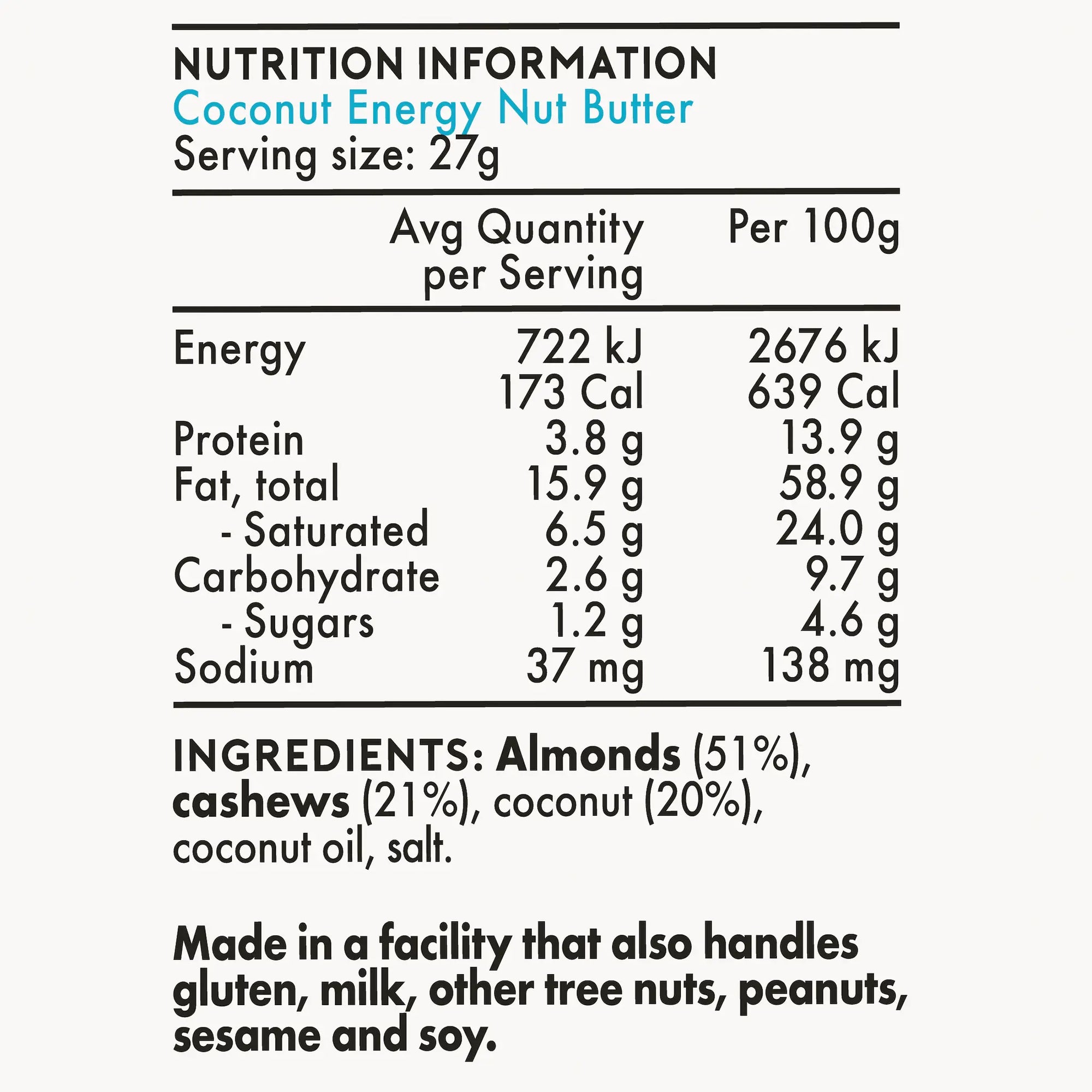

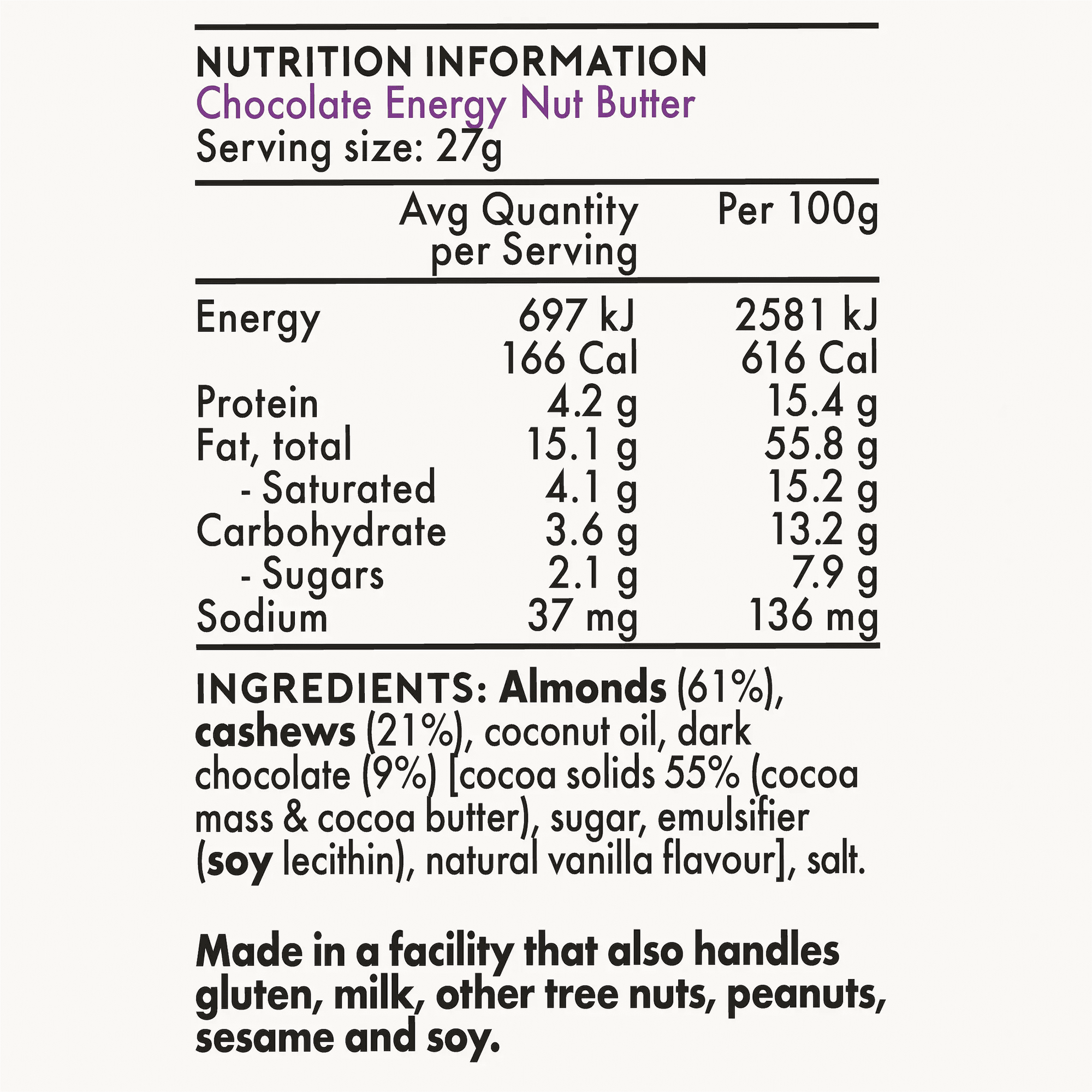

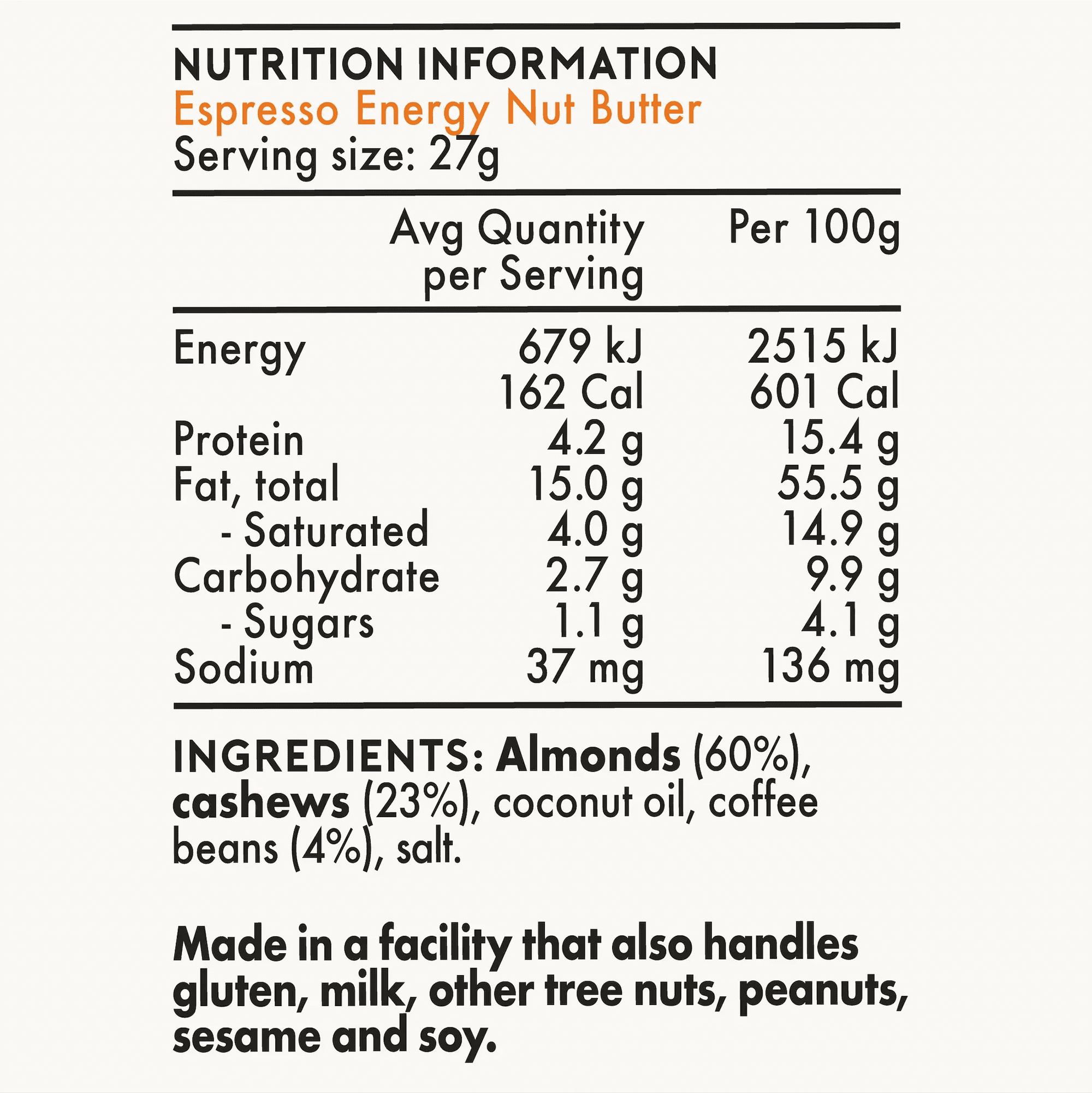

You can use effervescent electrolyte tablets and powders, or electrolyte drinks that are mixed with carbohydrate for fuel. You can even eat salty foods – chips, pretzels, salted nuts, or Energy Nut Butter!

Salt capsules and tablets are also an option during long endurance efforts. Note that these products may cause gut discomfort and nausea in some cases.

This is because the high concentration of sodium can slow stomach emptying. Salt tablets can be more irritating for the gut, so capsules could be a safer option for you.

Most distance races prohibit the use of ibuprofen. The reason is for your safety.

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory (NSAIDs) reduce blood flow to the kidneys. Kidneys have an important role in managing hydration levels and electrolyte balance. If your kidney function is affected, it can exacerbate the risk of both hyponatremia and dehydration and lead to kidney damage.

Examples of NSAIDs include ibuprofen (Neurofen, Advil) and aspirin.

Multiple studies have looked at athletes and their hydration status after finishing a race.

Check out the Consensus Statement for Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia for a full list of studies. Some studies looking at overhydration and hyponatremia across different sports found:

- The highest reported incidence of asymptomatic hyponatremia (i.e. overhydration) post-race has been consistently noted in 100 mile runs, where the incidence rate has ranged from 5% to 51% of runners.

- Incidence rates in Ironman triathlons in different environments has ranged from negligible to as high as 25% of participants.

- Studies on endurance cyclists have shown the incidence of asymptomatic hyponatremia has ranged from 0% to as high as 12%.

- Reported incidences at the marathon distance (42.2km) have ranged from 0% to as high as 13% of race finishers.

EAH is determined by measuring the sodium levels in your blood. The normal range is 135-145 mEq/L.

A measure of 125 mEq/L is considered low and indicates overhydration. A sodium serum level below 120 mEq/L is considered serious and could cause symptoms like seizures.